THE SCALE OF THE UNIVERSE—THE SOLAR SYSTEM

§ 1

The story of the triumphs of modern science naturally opens with Astronomy. The picture of the Universe which the astronomer offers to us is imperfect; the lines he traces are often faint and uncertain. There are many problems which have been solved, there are just as many about which there is doubt, and notwithstanding our great increase in knowledge, there remain just as many which are entirely unsolved.

The problem of the structure and duration of the universe [said the great astronomer Simon Newcomb] is the most far-reaching with which the mind has to deal. Its solution may be regarded as the ultimate object of stellar astronomy, the possibility of reaching which has occupied the minds of thinkers since the beginning of civilisation. Before our time the problem could be considered only from the imaginative or the speculative point of view. Although we can to-day attack it to a limited extent by scientific methods, it must be admitted that we have scarcely taken more than the first step toward the actual solution.... What is the duration of the universe in time? Is it fitted to last for ever in its present form, or does it contain within itself the seeds of dissolution? Must it, in the course of time, in we know not how many millions of ages, be transformed into something very different from what it now is? This question is intimately associated with the question whether the stars form[Pg 10] a system. If they do, we may suppose that system to be permanent in its general features; if not, we must look further for our conclusions.

The Heavenly Bodies

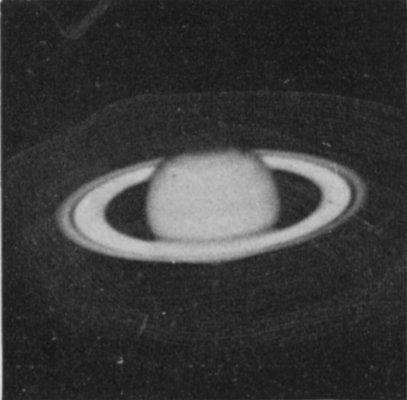

The heavenly bodies fall into two very distinct classes so far as their relation to our Earth is concerned; the one class, a very small one, comprises a sort of colony of which the Earth is a member. These bodies are called planets, or wanderers. There are eight of them, including the Earth, and they all circle round the sun. Their names, in the order of their distance from the sun, are Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and of these Mercury, the nearest to the sun, is rarely seen by the naked eye. Uranus is practically invisible, and Neptune quite so. These eight planets, together with the sun, constitute, as we have said, a sort of little colony; this colony is called the Solar System.

The second class of heavenly bodies are those which lie outside the solar system. Every one of those glittering points we see on a starlit night is at an immensely greater distance from us than is any member of the Solar System. Yet the members of this little colony of ours, judged by terrestrial standards, are at enormous distances from one another. If a shell were shot in a straight line from one side of Neptune's orbit to the other it would take five hundred years to complete its journey. Yet this distance, the greatest in the Solar System as now known (excepting the far swing of some of the comets), is insignificant compared to the distances of the stars. One of the nearest stars to the earth that we know of is Alpha Centauri, estimated to be some twenty-five million millions of miles away. Sirius, the brightest star in the firmament, is double this distance from the earth.

We must imagine the colony of planets to which we belong as a compact little family swimming in an immense void. At distances which would take our shell, not hundreds, but millions[Pg 11] of years to traverse, we reach the stars—or rather, a star, for the distances between stars are as great as the distance between the nearest of them and our Sun. The Earth, the planet on which we live, is a mighty globe bounded by a crust of rock many miles in thickness; the great volumes of water which we call our oceans lie in the deeper hollows of the crust. Above the surface an ocean of invisible gas, the atmosphere, rises to a height of about three hundred miles, getting thinner and thinner as it ascends.

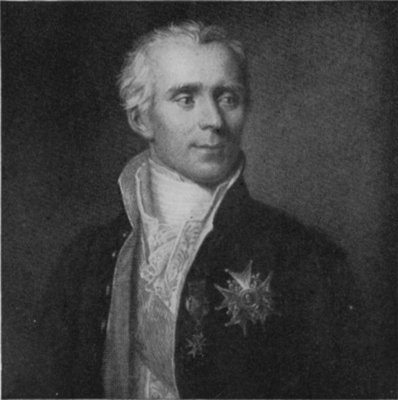

LAPLACE

One of the greatest mathematical astronomers of all time and the originator of the nebular theory.

Photo: Royal Astronomical Society.

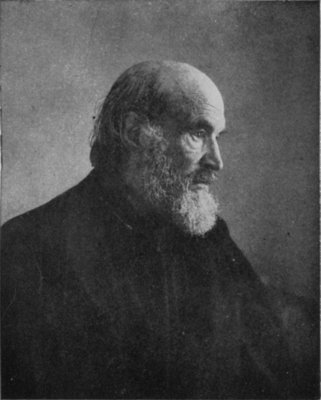

PROFESSOR J. C. ADAMS

who, anticipating the great French mathematician, Le Verrier, discovered the planet Neptune by calculations based on the irregularities of the orbit of Uranus. One of the most dramatic discoveries in the history of Science.

Photo: Elliott & Fry, Ltd.

PROFESSOR EDDINGTON

Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge. The most famous of the English disciples of Einstein.

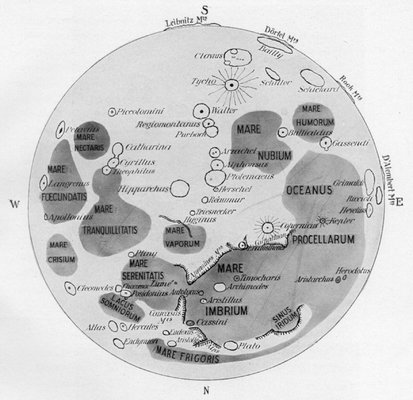

FIG. 1.—DIAGRAMS OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM

THE COMPARATIVE DISTANCES OF THE PLANETS

(Drawn approximately to scale)

The isolation of the Solar System is very great. On the above scale the nearest star (at a distance of 25 trillions of miles) would be over one half mile away. The hours, days, and years are the measures of time as we use them; that is: Jupiter's "Day" (one rotation of the planet) is made in ten of our hours; Mercury's "Year" (one revolution of the planet around the Sun) is eighty-eight of our days. Mercury's "Day" and "Year" are the same. This planet turns always the same side to the Sun.

THE COMPARATIVE SIZES OF THE SUN AND THE PLANETS

(Drawn approximately to scale)

On this scale the Sun would be 17½ inches in diameter; it is far greater than all the planets put together. Jupiter, in turn, is greater than all the other planets put together.

Except when the winds rise to a high speed, we seem to live in a very tranquil world. At night, when the glare of the sun passes out of our atmosphere, the stars and planets seem to move across the heavens with a stately and solemn slowness. It was one of the first discoveries of modern astronomy that this movement is only apparent. The apparent creeping of the stars across the heavens at night is accounted for by the fact that the earth turns upon its axis once in every twenty-four hours. When we remember the size of the earth we see that this implies a prodigious speed.

In addition to this the earth revolves round the sun at a speed of more than a thousand miles a minute. Its path round the sun, year in year out, measures about 580,000,000 miles. The earth is held closely to this path by the gravitational pull of the sun, which has a mass 333,432 times that of the earth. If at any moment the sun ceased to exert this pull the earth would instantly fly off into space straight in the direction in which it was moving at the time, that is to say, at a tangent. This tendency to fly off at a tangent is continuous. It is the balance between it and the sun's pull which keeps the earth to her almost circular orbit. In the same way the seven other planets are held to their orbits.

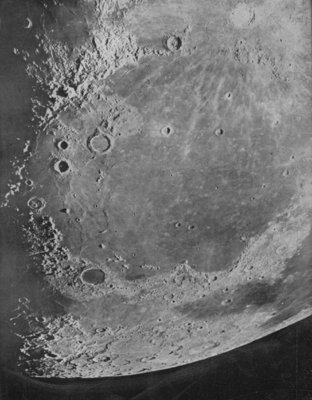

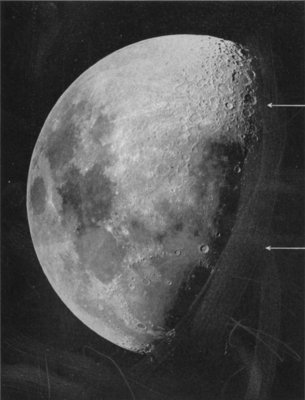

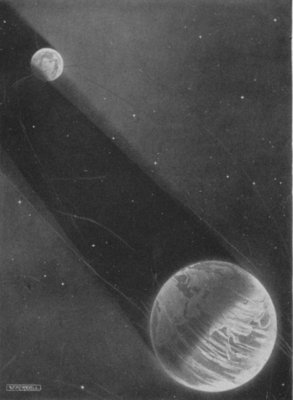

Circling round the earth, in the same way as the earth circles round the sun, is our moon. Sometimes the moon passes directly between us and the sun, and cuts off the light from us.[Pg 12] We then have a total or partial eclipse of the sun. At other times the earth passes directly between the sun and the moon, and causes an eclipse of the moon. The great ball of the earth naturally trails a mighty shadow across space, and the moon is "eclipsed" when it passes into this.

The other seven planets, five of which have moons of their own, circle round the sun as the earth does. The sun's mass is immensely larger than that of all the planets put together, and all of them would be drawn into it and perish if they did not travel rapidly round it in gigantic orbits. So the eight planets, spinning round on their axes, follow their fixed paths round the sun. The planets are secondary bodies, but they are most important, because they are the only globes in which there can be life, as we know life.

If we could be transported in some magical way to an immense distance in space above the sun, we should see our Solar System as it is drawn in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 1), except that the planets would be mere specks, faintly visible in the light which they receive from the sun. (This diagram is drawn approximately to scale.) If we moved still farther away, trillions of miles away, the planets would fade entirely out of view, and the sun would shrink into a point of fire, a star. And here you begin to realize the nature of the universe. The sun is a star. The stars are suns. Our sun looks big simply because of its comparative nearness to us. The universe is a stupendous collection of millions of stars or suns, many of which may have planetary families like ours.

§ 2

The Scale of the Universe

How many stars are there? A glance at a photograph of star-clouds will tell at once that it is quite impossible to count them. The fine photograph reproduced in Figure 2 represents[Pg 13] a very small patch of that pale-white belt, the Milky Way, which spans the sky at night. It is true that this is a particularly rich area of the Milky Way, but the entire belt of light has been resolved in this way into masses or clouds of stars. Astronomers have counted the stars in typical districts here and there, and from these partial counts we get some idea of the total number of stars. There are estimated to be between two and three thousand million stars.

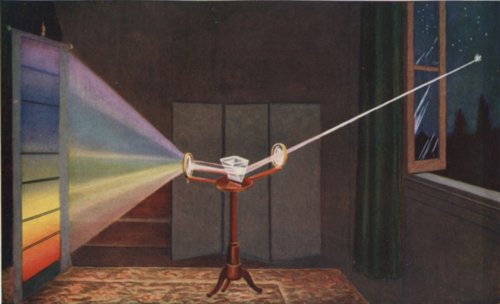

Yet these stars are separated by inconceivable distances from each other, and it is one of the greatest triumphs of modern astronomy to have mastered, so far, the scale of the universe. For several centuries astronomers have known the relative distances from each other of the sun and the planets. If they could discover the actual distance of any one planet from any other, they could at once tell all the distances within the Solar System.

The sun is, on the latest measurements, at an average distance of 92,830,000 miles from the earth, for as the orbit of the earth is not a true circle, this distance varies. This means that in six months from now the earth will be right at the opposite side of its path round the sun, or 185,000,000 miles away from where it is now. Viewed or photographed from two positions so wide apart, the nearest stars show a tiny "shift" against the background of the most distant stars, and that is enough for the mathematician. He can calculate the distance of any star near enough to show this "shift." We have found that the nearest star to the earth, a recently discovered star, is twenty-five trillion miles away. Only thirty stars are known to be within a hundred trillion miles of us.

This way of measuring does not, however, take us very far away in the heavens. There are only a few hundred stars within five hundred trillion miles of the earth, and at that distance the "shift" of a star against the background (parallax, the astronomer calls it) is so minute that figures are very uncertain. At this point the astronomer takes up a new method. He learns the[Pg 14] different types of stars, and then he is able to deduce more or less accurately the distance of a star of a known type from its faintness. He, of course, has instruments for gauging their light. As a result of twenty years work in this field, it is now known that the more distant stars of the Milky Way are at least a hundred thousand trillion (100,000,000,000,000,000) miles away from the sun.

Our sun is in a more or less central region of the universe, or a few hundred trillion miles from the actual centre. The remainder of the stars, which are all outside our Solar System, are spread out, apparently, in an enormous disc-like collection, so vast that even a ray of light, which travels at the rate of 186,000 miles a second, would take 50,000 years to travel from one end of it to the other. This, then is what we call our universe.

Are there other Universes?

Why do we say "our universe"? Why not the universe? It is now believed by many of our most distinguished astronomers that our colossal family of stars is only one of many universes. By a universe an astronomer means any collection of stars which are close enough to control each other's movements by gravitation; and it is clear that there might be many universes, in this sense, separated from each other by profound abysses of space. Probably there are.

For a long time we have been familiar with certain strange objects in the heavens which are called "spiral nebulæ" (Fig 4). We shall see at a later stage what a nebula is, and we shall see that some astronomers regard these spiral nebulæ as worlds "in the making." But some of the most eminent astronomers believe that they are separate universes—"island-universes" they call them—or great collections of millions of stars like our universe. There are certain peculiarities in the structure of the Milky Way which lead these astronomers to think that our universe may be[Pg 15] a spiral nebula, and that the other spiral nebulæ are "other universes."

FIG. 3—THE MOON ENTERING THE SHADOW CAST BY THE EARTH

The diagram shows the Moon partially eclipsed.

Vast as is the Solar System, then, it is excessively minute in comparison with the Stellar System, the universe of the Stars, which is on a scale far transcending anything the human mind can apprehend.